Happy Halloween, everyone! And to my Pagan followers, Blessed Samhain!

Author: Mark Z. Danielewski

Edition: Paperback; 2-Color (house appears in blue)

Publisher: Pantheon Books (2000)

Pages: 709

Challenges: Read Me Baby, One More Time; GoodReads 2011 Reading Challenge

How I Came by This Book: The first time I read House of Leaves, I borrowed my friend Amanda's full-color copy, after both she and one of my exes (neither of whom have ever met the other and who are as different as night and day) recommended it to me. The copy I read this time is my own, which was given to me by a friend who had gotten it from a friend.

House of Leaves was first being passed around, it was nothing more than a badly bundled heap of paper, parts of which would occasionally surface on the Internet. No one could have anticipated the small but devoted following this terrifying story would soon command. Starting with an old assortment of marginalized youth--musicians, tattoo artists, programmers, strippers, environmentalists, and adrenaline junkies--the book eventually made its way into the hands of the older generations, who not only found themselves in those strangely arranged pages but also discovered a way back into the lives of their estranged children.

No, for the first time, this astonishing novel is made available in book form, complete with the original colored words, vertical footnotes, and newly added second and third appendices.

The story remains unchanged, focusing on a young family that moves into a small home on Ash Tree Lane where they discover something terribly wrong: their house is bigger on the inside than it is on the outside.

Of course, neither Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist Will Navidson nor his companion Karen Green was prepared to face the consequences of that impossibility, until the day their two little children wandered off and their voices eerily began to return another story--of creature darkness, of an ever-growing abyss behind a closet door, and of that unholy growl which soon enough would tear through their walls and consume all of their dreams.

Review: People have said a lot of things about House of Leaves, but one descriptor that comes up over and over again is, if you'll pardon my French, "mind-fuck." This book is exactly that. A psychological novel that explores the unknown nature of darkness and the toll that it can take on the human mind, House of Leaves has the distinction of being one of those books that, as clichéd as it sounds, I'd dub "life-altering." Despite the fact that I'm a night owl and that I'm not easily spooked, after reading this book the first time, I looked at closets and dark corners with trepidation for months. In addition to this new-found (but temporary) uneasiness, I found that this book also changed my perceptions of insanity, loneliness, and, yes, the usefulness of footnotes.

The book tells a three-fold story. The main narrative is about Will Navidson, Karen Green, and their new home on Ash Tree Lane. Shortly after moving in they discover that the dimensions of the inside of their house are bigger than those of the outside. The secondary narrative is that of Johnny Truant, a drug-addled young man who finds and assembles the manuscript of a scholarly book written about a non-existent film about the house, titled The Navidson Record, after his friend's neighbor, Zampanó, dies. The tertiary narrative surrounds the late Zampanó and is inextricably linked with both The Navidson Record and Johnny Truant's story. I think it's safe to say that already you can tell that this is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. What Danielewski/Zampanó/Johnny Truant do with this riddle is even more impressive.

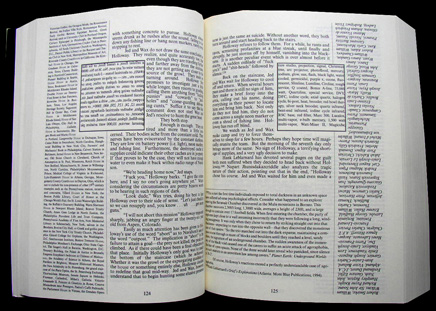

When people discuss this book, inevitably the novel's structure is one of the first things they talk about. And with good reason. Much like The Invention of Hugo Cabret used images to tell much of the narrative, so House of Leaves uses words to create images. Part of the reason why many people are reluctant to read this novel is because its sheer size is intimidating and because they see images like this:

Part of the chapter in which an expedition is launched inside the house to tackle the large spiral staircase that has grown within the dark and expansive interior, Danielewski uses footnotes in order to give the reader the impression that they too are walking down a never-ending staircase. Yet, for every page like this, there are pages like this:

Sitting on its side it doesn't look like much, but when you flip the book, it becomes a ladder of words, reflecting a ladder which one of the characters climbs in the book. There are even pages that have maybe one or two words on them, which means that for every page it takes you several minutes to read, there are entire sections of the book that you can get through in under a minute. But enough about the book's structure.

The plot itself is deep and interesting and the dizzying shifts between Zampanó's original text and Johnny Truant's footnote intrusions brings a uniqueness not found in other books. By making connections between the book and his own life, Truant subtly suggests to readers that there are connections to be made in their own lives. And there are. The characters that fill the pages of The Navidson Record are easy to relate to, which is quite a feat considering that their development is not constructed through a first person narrative like Johnny's but through a third person outside observer who shifts his focus from their troubles to anything from carbon dating to the story of Jacob and Esau.

Some have called House of Leaves a gimmick, but I prefer to see it as a refreshing break from the ordinary novel. Danielewski is a talented writer who uses both fact and fiction to create a terrifying story of family problems and personal struggles. This is not a story of monsters and boogeymen; it is far more chilling than that. House of Leaves is a book about how the extraordinary can either destroy a man or make him stronger. Just as it leaves the characters forever changed, it will leave the reader affected as well.

I'm giving House of Leaves 5 out of 5 Gabriels.

-Gabe